|

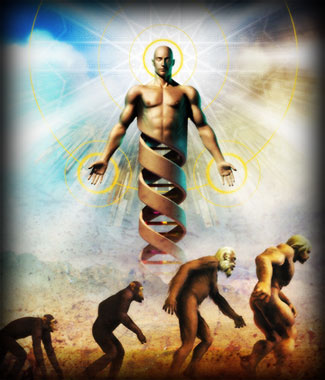

Humans have moved into the evolutionary fast lane and are becoming increasingly different, a genetic study suggests.

In the past 5,000 years, genetic change has occurred at a rate roughly 100 times higher than any other period, say scientists in the US.

This is in contrast with the widely-held belief that recent human evolution has halted.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Professor Henry Harpending, an author of the study from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, US, said: "The dogma has been these [differences] are cultural fluctuations, but almost any temperament trait you look at is under strong genetic influences.

"Genes are evolving fast in Europe, Asia and Africa, but almost all of these are unique to their continent of origin," he added. "We are getting less alike, not merging into a single, mixed humanity."

This is happening, he said, because "there has not been much flow" between different regions since modern humans left Africa to colonise the rest of the world. And there is no evidence that it is slowing down, he added.

"The technology can't detect anything beyond about 2,000 years ago, but we see no sign of [human evolution] slowing down. So I would suspect it is continuing," he told BBC News.

New gene selection

Researchers found evidence of recent selection in 7% of all human genes, including lighter skin and blue eyes in northern Europe and partial resistance to diseases, such as malaria, among some African populations.

"Five thousand years is such a small sliver of time," said co-author Professor John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "It's 100 or 200 generations ago. That's how long since some of these genes originated, and today they are [in] 30% or 40% of people because they've had such an advantage."

The researchers propose that there are two factors causing human evolution to speed up.

"One of them is there are a lot more people - the more people you have the more opportunities there are for an advantageous mutation to show up," said Professor Harpending.

A large population has more genetic variation and allows for more positive selection than a small one.

"The second is environmental change - our diets have changed, we are in radically new environments," he added. "With a large population size comes lots of new diseases."

Happening now?

However, geneticist Professor Steve Jones of University College London said suggesting a large population size could increase the speed of evolution was "a contentious issue".

"Once a population gets above a very small size it is not very clear if its ability to respond to natural selection depends on size," he told BBC News.

"The general picture that evolution has speeded up in the last 10,000 years as we change from, to put it bluntly, being animals to being humans is clearly true," he explained. "To suggest it is happening at this instant, I would suggest, is probably wrong."

He said natural selection needed difference - either in the ability to stay alive or in the number of offspring born.

"The fundamental observation is that this difference has gone," said Professor Jones.

"At the moment we are in an evolutionary interval. We are in between two storms. One storm has more or less blown itself out, the storm of farming.

"The question is whether we are going to stay in the calms or whether another great storm will start. And if there is one, I would say it is most certainly to do with epidemic disease."

How they did it

The study looked specifically at genetic variations called "single nucleotide polymorphisms," or SNPs. These are single-point mutations, or changes, in the genetic sequence of DNA on chromosomes.

If the mutation is advantageous then it will spread rapidly in the population, along with DNA on either side of the mutation.

The authors argued that if the same chromosome from numerous people had a segment with an identical pattern of SNPs this would indicate that the segment of the chromosome had not been broken up (recombined) recently.

Therefore, a gene on that segment of chromosome must have evolved recently and fast, they believe. If it had evolved long ago, the chromosome would have broken up and recombined.

Article from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7132794.stm

|